THE WINE MAKER’S ROLE : It would be daft, though, to imply that winemakers were in any way redundant. Wine left to make itself would in most cases soon be bacterially spoiled -on its way to vinegar- because once it has finished fermenting it needs to be protected from oxygen.

But, as the pendulum has swung more towards the role of the grower in the vineyard in determining quality, so it has swung away from the winemaker as interventionist wizard, a role which reached its apogee in some of the high-tech wineries of California and Australia in the 1970s and 1980s.

MAKING RED WINE

Crushing

Once picked, the aim is to get all grapes to the winery as quickly and as smoothly as possible – ideally, although this is usually more important for white grapes, transported in stacks of small plastic crates, rather than in one heavy mass in the back of a huge truck where the bunches at the bottom will get squashed by those above. At the winery most red grapes are put through a “crusher” to break the skins and gently release the juices ready for fermentation, and, depending on the grape variety and region, to remove all or some of the bitter, tannic stems (some are often left on in Burgundy, but they are almost always removed in Bordeaux).

The principal exceptions to the crushing rule are red grapes for sparkling wines, Beaujolais, and other bright, fruity reds intended to be drunk young, and some burgundy. Here the whole bunches are fermented. The best red grapes of the Douro, destined for long-lived vintage port, are also treated differently.

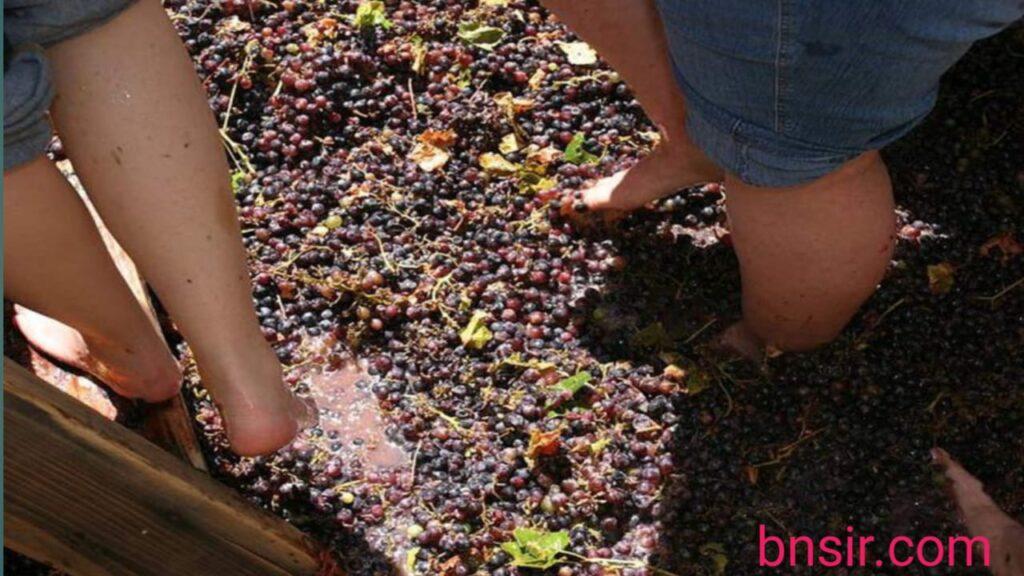

Many port producers, having tried mechanical alternatives, have come back to old-fashioned treading – by warm and gentle human feet – although some find that feet are even more effective if the grapes have been given a swift preliminary pre-crush by machine.

The Wine Fermentation

After crushing, the “must”, the pulp of skins, and juice, is fed into fermentation containers which vary from traditional open-topped wood vats to glass-lined cement and fibreglass (neither usually associated with the highest quality wines) to giant, stainless steel tanks to, in a few cases, wooden barrels.

A small amount of sulphur dioxide, as protection against oxidation and as an antiseptic, may be added if it was not added at the crusher stage, but this is more especially needed for white wines. In cooler climates, such as the main French wine regions, sugar (chaptalization) or concentrated grape must (enrichment) may be added to both reds and whites to bring the potential alcohol up to a reasonable level.

And in many regions, particularly warm New World ones, acid may be added, although, again, this balance adjustment is more usually applied to white wines.

To get fermentation started immediately a winemaker has several options. In cool climates, he might heat the must, and he might use yeast activators and/or cultured yeasts. These are much more reliable than wild strains, but the argument against them is that, in dispensing with the indigenous yeasts in favour of laboratory-cultured ones, you lose some of the regional individuality of wine.

(This is particularly the case with the malleable Chardonnay grape, for which there are some very popular – in the New World-Burgundy-type cultured yeasts giving extra rich, buttery flavours and others that give notably fruity flavours.)

When fermentation is underway, stopping the temperature from rising too high is crucial. Over-hot musts produce coarse, stewed-tasting wines and, if the temperature gets completely out of control, the yeasts will be killed off before they have finished converting sugar into alcohol.

Most reds are therefore fermented somewhere between 25-30°C (77-86 F). The other essential during red wine fermentation is to keep the skins submerged, so that their colour (the flesh of most red wine grapes is as colourless as that of white grapes), tannin, and flavours are leached out into the liquid.

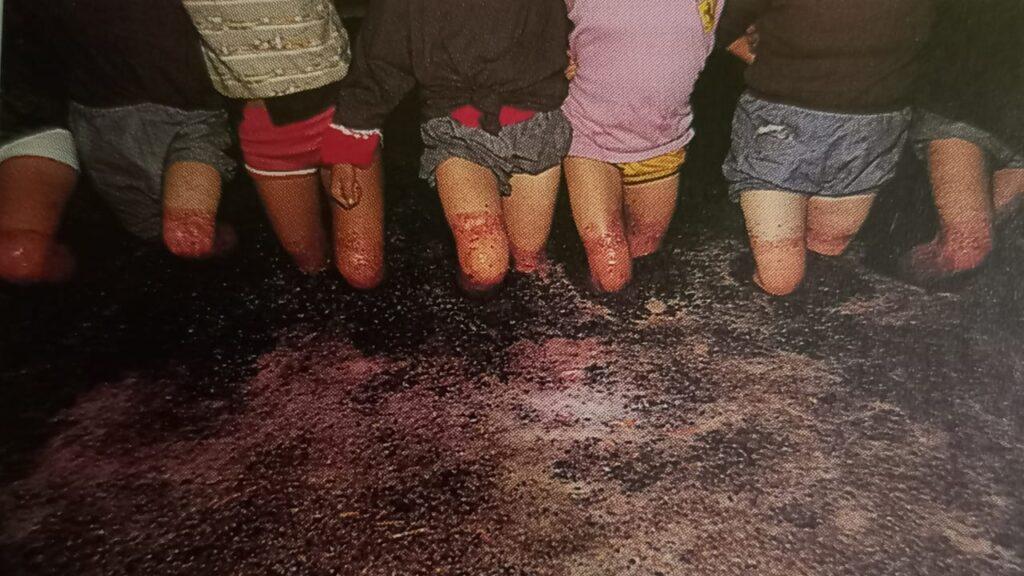

Carbon dioxide given off by the yeasts constantly pushes the skins to the top, so they need to be pulled down again regularly, either by pumping the juice up and over or by punching them down by hand or mechanically.

Fermentation may take only a few days, but if so, the results will be light reds for early consumption. More serious reds are more likely to take two weeks and may be left macerating with their skins for three or more. The wine will then be drawn off the skins (although this can also be done part way through fermentation to make a less tannic wine) and the skins will be pressed.

The winemaker may then add some, or all, of this sturdy, tannic “press wine” to give the original wine more body, or he may leave the decision until spring.

Malolactic fermentation

The final stage of fermentation for all reds (but only some whites) is the “malolactic fermentation”, the conversion of astringent malic acid into softer lactic acid. Nowadays this is usually induced (by adding appropriate bacteria) straight after the alcoholic fermentation, but some traditional and non-interventionist winemakers allow it to happen of its own accord when temperatures begin to rise in the spring.

In theory the wine is now ready to drink. In practice most red wines need time to soften, but those intended for immediate drinking will be fined and filtered to remove sediment and any other foreign bodies prior to bottling.

Oak

Most of the world’s serious red wines are matured in new oak barrels for between four and twenty-four months to soften the tannins and develop that elusive attribute- complexity. And preferably the oak is French, because France, with everything else going for it, also manages to have the finest oak, from forests such as Allier, Nevers, and Limousin.

New oak gives flavour (especially vanillin) and tannin, and, being porous, allows limited, but significant, ben- eficial interaction between wine and air.

The age of the barrel is fundamental: the newer the barrel, the more it gives to the wine, so after three or four years it has little left to impart. Another important variable is its charring, or “toast”: the higher the toast the more toasty the flavour.

Compared with French oak, American tends to be less subtle, with a stronger vanilla-and-spice taste, as does Slovenian. The advantage of these and other woods such as chestnut and acacia is that they are cheaper. But nowadays there are cheap ways to get new-oak flavour:

oak chips and oak staves canbe suspended in stainless steel tanks or old oak vats to give a quick oak fix. It doesn’t make for subtlety and is much frowned on in classic European regions, but gives a simple toasty-oak flavour to wines for early drinking.

Final stages

During wood ageing, the winemaker still has a few crucial tasks. Most barrels need to be topped up periodically to compensate for evaporation and the wine must be “racked”. This is the drawing off of wine from one barrel to a clean one, leaving behind the sediment that has been deposited (the number of rackings depending on the duration in barrel and the type of wine).

Some wines also need to be blended. This may be because they are made from more than one grape variety (claret, for example), or because the winemaker has so far kept wine from different vineyards separate. Before bottling, the wine will be fined to remove impurities, either traditionally with egg white or with a commerical clarifying agent such as bentonite.

Most wines will also be filtered, to further ensure their stability. although top producers, especially in Burgundy, the Rhône, and California, often dispense with filtration on the grounds that it strips wines of character.

Red wine: the vital stages

1 TREADING OR CRUSHING THE GRAPES

Treading, the traditional method for vintage port, is not just a quaint custom put on for the benefit of visitors, but the best way to extract the maximum colour and tannin from the skins in a short time.

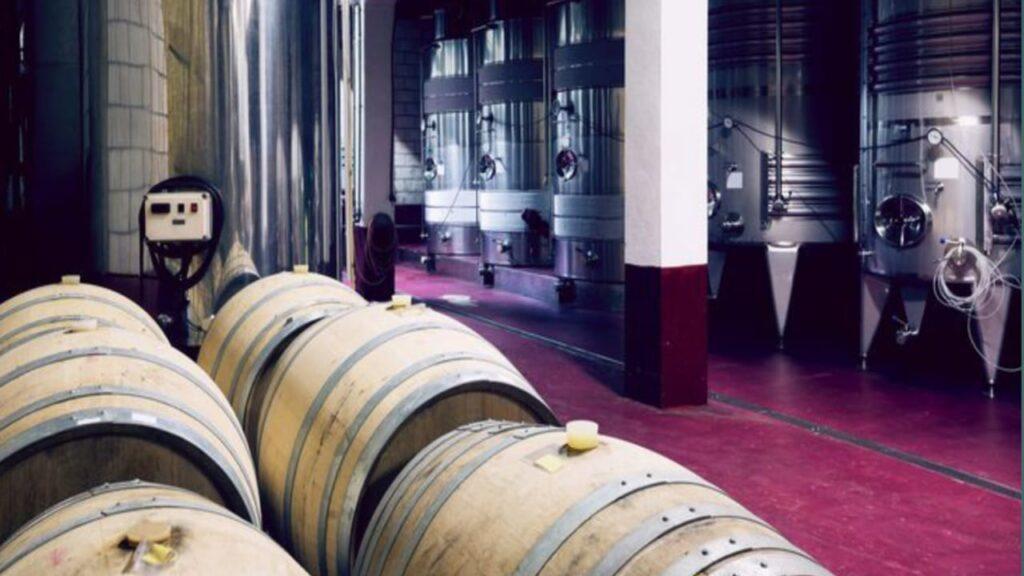

2 FERMENTATION

Either in closed vats or open-topped vessels. Temperatures may be carefully controlled or they may not. Whichever approach, this is the stage where yeasts convert grape sugar into alcohol and therefore juice into wine.

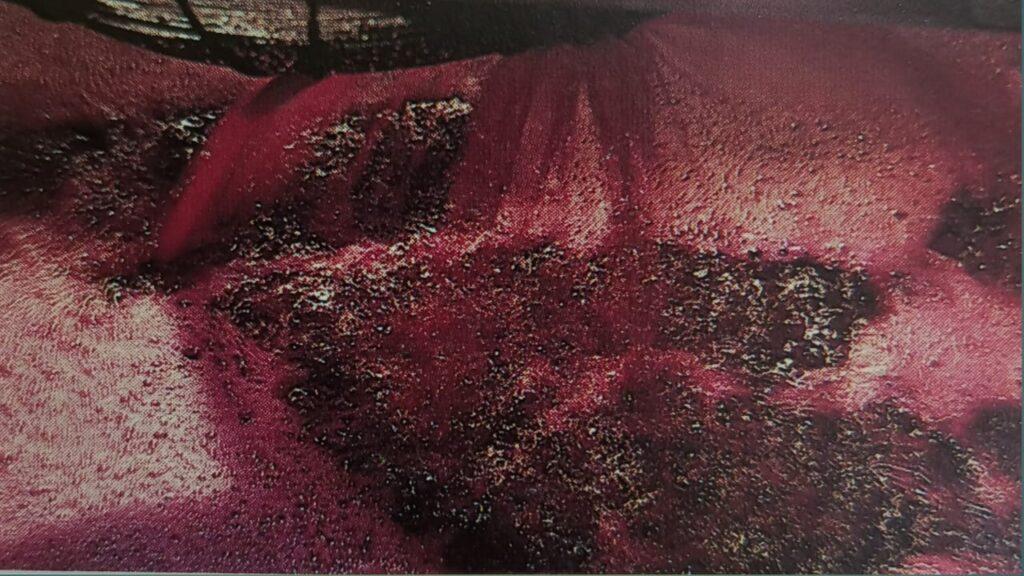

3 SUBMERGING THE SKINS

During fermentation a “cap” of skins rises to the top of the bubbling mass and has to be pushed down regularly, either mechanically or by prodding with a pole, to ensure colour leaches out of the skins into the liquid.

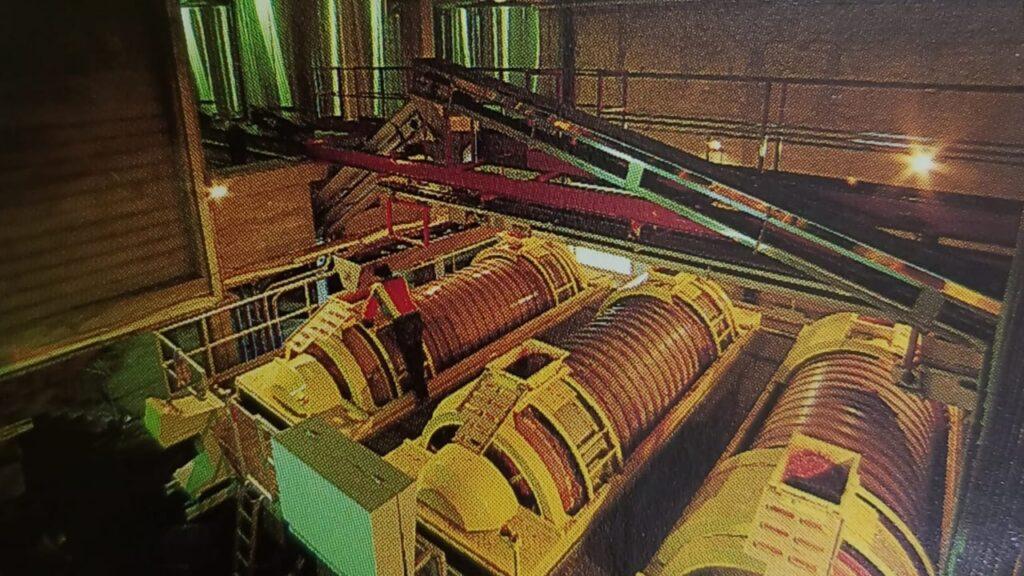

4 PRESSING

Red wine grapes are crushed before fermentation but pressing is carried out afterwards. The left- over pulpy grape mass is put through a press to yield tannic “press wine” – which may or may not be blended in to improve the final wine.

5 MATURATION

Most of the better red wines – especially those intended to improve with age-are at least partially aged in new oak barrels for depth and complexity. A new trend is to ferment, or partly ferment, them in these barrels.

6 RACKING

As they mature, red wines drop a sediment – they are removed from this in a process called racking, in which the wine is moved gently from one barrel to another clean one… the final transfer is to the bottling line.

Tannin

There is much debate in the wine world about whether today’s great red wines from the classic regions-claret, burgundy, Rhône, Barolo-will last as long as their predecessors, and the ripeness, or softness, of the tannins is at the heart of the debate.

Tannin, the dry. slightly bitter, mouth-coating substance that makes cold tea so unpleasant, is essential for wine, especially red, that is going to be aged (whites rely more on acidity), but winemakers since the 1980s have been aiming for less aggressively tannic wines-wines, simply, that are suppler and ready for drinking sooner.

They achieve this by picking the grapes later, so that the tannins in the skins, stalks, and pips are all riper; by removing the stalks, which contain tannins that are more bitter than those in the skins; and by crushing gently, so that the pips, which contain the harshest tannins of all, are not split.

And, if maturing the wine in wood, which is another source of tannin, they make sure that they buy good barrels, made from well-seasoned, properly toasted oak, and they are careful not to leave the wine in them for too long. But none of this answers the fundamental question as to whether contemporary classics will last as long as their predecessors.

The winemakers say they will, because tannins are present, although different, but they would say that, wouldn’t they? Only time will tell.

THE WINE MAKER’S ROLE understand by YouTube Vedio🎬